Early access to AAC can transform how children connect, learn and communicate. I have seen this first-hand through my work with children like Lottie, who began using an eye-gaze device, the Grid Pad 13, before starting school.

When we first started working together, she found it hard to engage with toys or games. Switch toys, videos and even interactive software did not hold her attention for long. What made a difference was people. Lottie communicates best through shared interaction, humour and connection.

So we built her learning around that.

Starting Small

During the summer, Lottie’s device was set to a 12-cell grid so that the buttons were large and easy to select. To build confidence, we started with something new but motivating, the Orchard Toys Shopping Game. The idea of choosing and collecting items felt purposeful and familiar from real life, even if the game itself was new. I adapted it by adding Velcro to the cards and trolley board so we could attach the pieces as we played and keep everything at the right angle for her eye gaze. It also solved a practical problem, as her tray wasn’t big enough for all the game pieces.

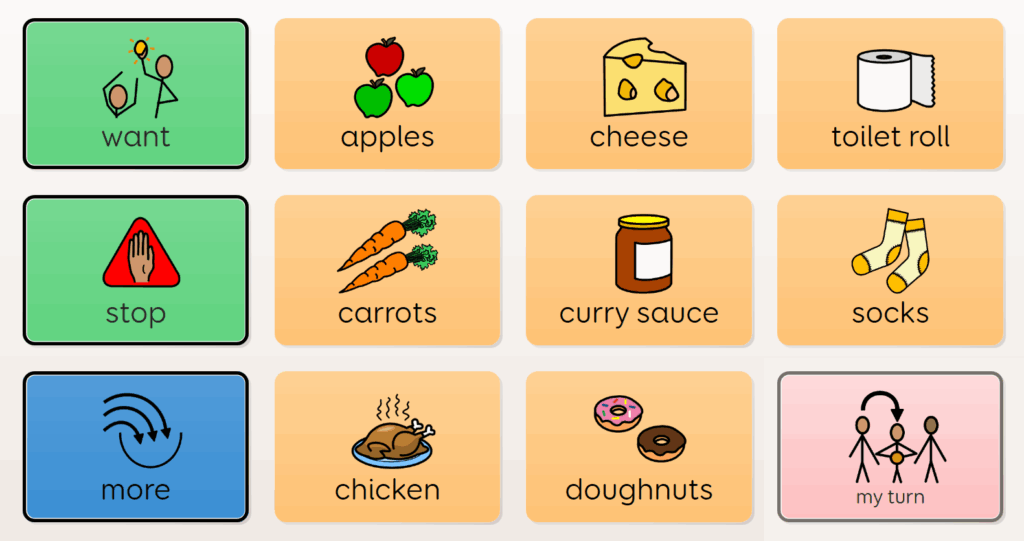

Her first grid included the game’s vocabulary, three core words, want, stop and more, plus a phrase, my turn. Before we played, we explored the words together. I would turn over a card and say, “Ooh, what is it? Apples!” Then I’d pause, wondering aloud, “Hmm, where are apples?” I’d glance at the screen, gesture towards it, and wait. If she didn’t find it after a moment, I’d model the word by selecting it myself. Over time, Lottie began to make these selections more quickly and confidently.

Play Becomes Learning

Once we had learned the words, we played. The aim was simple: find the picture, say what you want, and take your turn. Early on, Lottie focused on single words. I modelled short sentences like “Lottie want apples” or “more doughnuts”. It didn’t take long for her to begin combining words herself.

What stood out most was her understanding of symbols. The images on the cards looked different from those on the screen, yet Lottie could match them with ease. It reminded me how easily children adapt when we presume competence, and how quickly progress can happen when we trust their ability to make meaning.

Moments like these show why starting early matters. When AAC is introduced through play, children learn that communication is power, not a task but a shared experience.

Building Momentum

We met weekly, each session bringing a little more accuracy and attention. Her mum, Lauren, joined in every game, and they soon began playing it regularly at home too. Each week we made small changes, such as introducing a new vocabulary set or increasing the grid size, so the activity stayed fresh while building on what Lottie already knew. Lauren later said how hard it had been to find games that suited Lottie before, but now she had something that was fun, meaningful and easy to adapt.

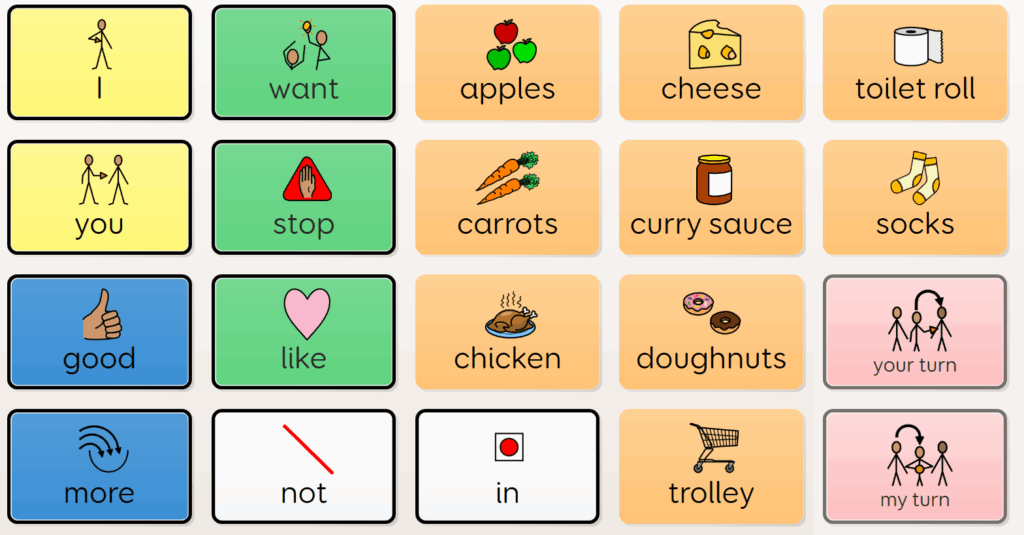

As we went on, I increased her grid size to 20 cells. This opened the door to longer sentences and more natural turn-taking. I began modelling combinations like “I want apples”, “apples in trolley”, or “your turn”. If I made a mistake, I modelled repair language too: “Not apples. I not want. You want apples?” It made the exchange more real, showing that communication isn’t about getting it right but about staying connected.

Finding the Right Fit

To keep her motivated, we adjusted technical settings too. Calibration improved when we switched from a cartoon bird to a picture of her favourite character, Mr Tumble. It may sound small, but those details matter. Attention, emotion and accuracy are all linked.

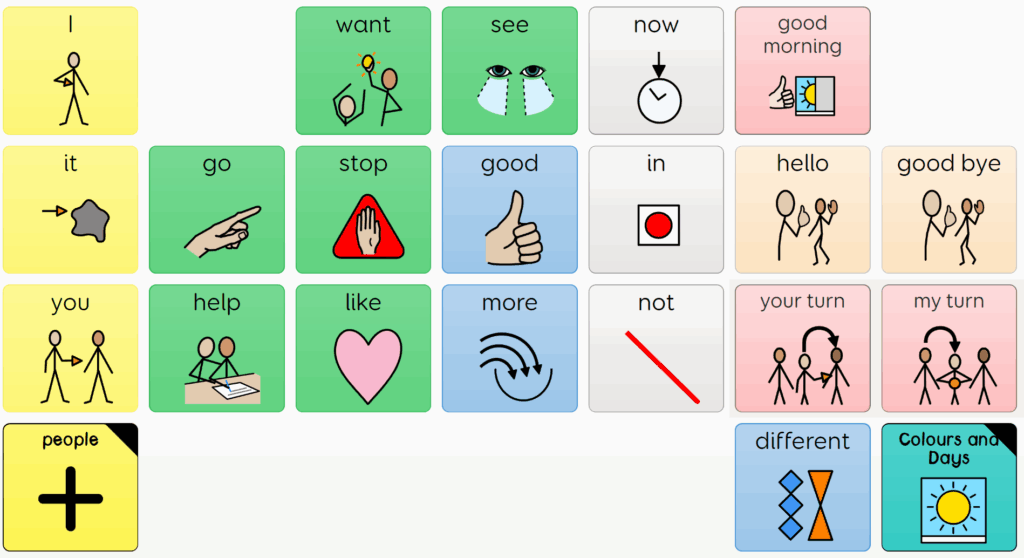

Today, Lottie is working confidently on a 28-cell grid. It follows the Super Core 30 layout, though without the speech bar, as our focus remains on functional, playful communication. She now takes part in shared reading and uses jump pages to explore new words and stories. At school, staff have built AAC into daily routines, from morning greetings to dinner choices, so her communication tools travel with her through the day.

Music as Motivation

Recently, we began using music to expand her vocabulary and confidence. During our song sessions, Lottie used her device to tell me how to play: quickly, slowly, loud, quiet. She laughed when I changed pace to match her choices. We built in plenty of pauses so she could use words like stop, go and different to take control.

In our last session, Lottie navigated jump pages independently to switch between song grids. This was a huge step forward. By introducing jump pages through songs, we can scaffold her learning and build navigation skills gradually, one meaningful context at a time. The combination of eye gaze, music and playful structure has made communication both motivating and purposeful.

A Shared Success

Lottie’s story reminds us that early AAC intervention can change everything. When communication tools are introduced through play and supported by teaching, families and schools, children gain not just words but confidence, connection and joy.

At AAC and Me, we believe that communication begins with connection. When play leads the learning and everyone around a child joins in, AAC becomes more than technology, it becomes a voice.

If your school, setting or family would like support to develop communication through AAC and assistive technology, get in touch to find out how we can help.

🌐 www.aacandme.co.uk

📧 info@aacandme.co.uk